From Prehistoric Hillforts to a Contemporary Mediterranean Destination

Introduction: Space, Stone, and Continuity

Today, Primošten is perceived as one of the most striking coastal settlements of central Dalmatia, recognizable for its old town core on a peninsula, stone-built vineyards, and strong tourist identity. However, the present-day appearance of the town represents only the final phase of a long historical process in which natural conditions, political circumstances, and human adaptation have been continuously intertwined. Understanding Primošten requires a perspective that goes far deeper than the last few centuries—it requires viewing space as a permanent living framework in which continuity of settlement can be traced back to prehistoric times.

The geographical position of Primošten is marked by pronounced contrasts. On one side lies the sea, which throughout history represented a source of food, communication, and trade, but also a threat in periods of instability. On the other side stretches a rugged karst hinterland, poor in arable land yet rich in stone, which for centuries served as the primary building material and the foundation of local architecture. It was precisely this relationship between sea and karst that shaped the historical destiny of the area of present-day Primošten.

This blog offers a comprehensive and systematic overview of the history of Primošten, written in an academic narrative style without formal scholarly citation apparatus, yet grounded in relevant historiography, archaeological research, and professional literature. The aim of the text is not to romanticize the past, but to clearly and calmly explain the processes that led to the formation of the present settlement—from prehistoric hillforts, through medieval hinterland communities and a fortified islet, to a modern tourist center.

Prehistoric Period: The First Traces of Settlement

The earliest layers of the history of the Primošten area reach back into prehistory, specifically the Bronze and Iron Ages. Although the present-day urban core of Primošten was not inhabited during this period, the wider area abounds in traces of early human communities that recognized the strategic and economic value of this landscape.

The key archaeological indicators of prehistoric settlement are the remains of hillforts—fortified sites located on elevated ground. These hillforts were not settlements in the modern sense of the word, but complex defensive and surveillance points that enabled territorial control, protection of the population, and supervision of important communication routes.

The hillforts were constructed using dry-stone techniques, without binding material, which required a high level of construction knowledge and organized labor. Their placement was not accidental: elevations with wide visibility were deliberately chosen, often combined with natural cliffs that further enhanced their defensive function.

Illyrian Hillforts in the Vicinity of Primošten

In the immediate surroundings of present-day Primošten, a significant number of prehistoric hillfort sites have been recorded, indicating relatively dense settlement and the strategic importance of this area during prehistory. Owing to its position between the coast and the more fertile hinterland, the region played an important role in controlling movement, communication, and the exchange of goods. Hillforts were not randomly established, but carefully positioned on elevations that provided broad visibility and mutual visual connectivity.

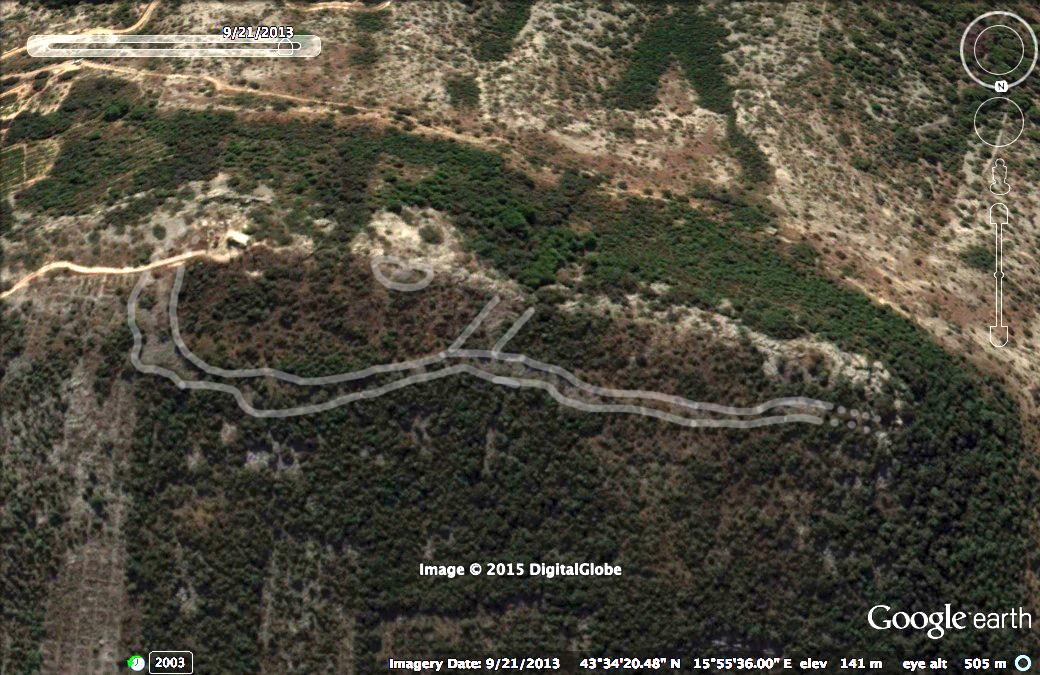

Among the most prominent sites are the hillfort on Mount Gaj (also known as the Kremik Hillfort) and the Okrubjak hillfort, along with a series of smaller yet functionally interconnected fortifications scattered throughout the hinterland of present-day Primošten. Together, these sites formed a defensive and surveillance system typical of the Bronze and Iron Ages along the eastern Adriatic coast, where communities were organized around fortified elevations serving as permanent or seasonal settlements.

Mount Gaj, which today dominates the landscape due to a modern religious monument, also held exceptional strategic and symbolic importance in prehistoric times. On its summit and slopes, preserved remains of dry-stone structures indicate the existence of a fortified settlement whose defensive walls followed the natural configuration of the terrain. The walls were built of locally sourced stone without mortar, a characteristic feature of prehistoric construction in this region.

Although modern interventions have partially altered the appearance of the summit plateau, the spatial context of the site still clearly indicates its original function. From Mount Gaj, it was possible to monitor a wide expanse of the hinterland as well as the coastal zone, confirming its role as a key surveillance point essential to the security of the community. Archaeological finds from the site, including fragments of prehistoric pottery, further confirm that the hillfort was not merely a temporary refuge but a space where everyday life activities took place.

The Okrubjak hillfort, located further inland to the north, represents one of the most impressive examples of prehistoric fortification in this part of Dalmatia. Its massive dry-stone ramparts encircling the hilltop testify to a high level of organization and prolonged habitation. The size and preservation of the walls suggest a community capable not only of defense, but also of planned spatial use adapted to natural conditions.

It is important to emphasize that such hillforts did not function as isolated structures. Rather, they formed an interconnected network of fortifications that enabled early detection of danger and communication across a broader area. Visual connectivity between the Kremik hillfort, Okrubjak, and smaller hillfort sites in the hinterland indicates the existence of an organized system of territorial control and defense, further underscoring the importance of the Primošten area in prehistoric times.

This spatial arrangement of hillforts and their internal logic laid the foundation for later settlement patterns and land use. Although the function of individual elevations changed with the arrival of the ancient and medieval periods, the continuity in selecting the same dominant landscape points testifies to long-term human adaptation and spatial understanding that began already in prehistory.

Satellite view of the prehistoric hillfort on Mount Gaj (Kremik), one of the key hillfort sites in the Primošten area

Tumuli and the Funerary Landscape

Alongside hillforts, an important element of the prehistoric landscape consists of stone mounds, or tumuli. Scattered throughout the hinterland near settlements such as Prhovo, Kruševo, and Široke, these structures represent burial mounds most commonly associated with Illyrian communities.

At first glance, tumuli may appear to be random piles of stones; however, their regular form, placement, and repetition across the landscape clearly indicate intentional construction. They testify to developed burial practices and social hierarchy within prehistoric communities, as well as to a symbolic relationship with space and death.

The Ancient Period: Roman Organization of Space and Landscape

With the arrival of the Romans on the eastern Adriatic coast, a new chapter begins in the history of the wider Primošten area. Although an urban center did not develop in the area of today’s old town core during antiquity, Roman rule left a deep and long-lasting imprint on the organization of the landscape, economy, and communication networks. Roman influence was particularly strong in the hinterland, where natural conditions proved suitable for agriculture, but also along the coast, which became part of important maritime routes.

After the complete incorporation of Dalmatia into the Roman Empire, this area entered an administrative and economic system characterized by rational planning and organization. Roman settlement patterns were not random; every location had a defined function within a broader system of governance, production, and trade. It was precisely this approach that enabled the long-term impact of Roman presence, traces of which can still be recognized today.

Roman Agrarian Colonization and the Transformation of the Hinterland

One of the most significant aspects of Roman presence in the area of present-day Primošten was agrarian colonization. The Romans recognized the potential of karst fields and gently rolling hinterland terrain where, despite demanding natural conditions, they established a system of agricultural production adapted to the Mediterranean environment.

In this context, villae rusticae are of particular importance—rural residential and economic complexes that served as centers of agricultural production. At several sites in the Primošten hinterland, remains of such estates have been identified, indicating a developed network of production units connected to larger urban centers in the region.

Villae rusticae were not merely places of residence, but complex economic systems. They typically included facilities for olive oil and wine production, storage spaces, work areas, and residential quarters. This organization testifies to the continuity of agricultural production, especially viticulture and olive cultivation, whose roots in this area can be traced back more than two thousand years.

It is important to emphasize that Roman agrarian presence did not imply the complete displacement of local populations, but rather their gradual integration into a new system. The Romans often relied on local knowledge of terrain and climate, enhancing it with their own technological and organizational solutions.

Map showing the locations of Roman villae rusticae in the wider Primošten area

Stone wall remains of a Roman villa rustica in the hinterland of Primošten

Vine and Olive Cultivation in the Ancient Context

In antiquity, the vine and the olive tree formed the foundation of Mediterranean agriculture, and the area of present-day Primošten was no exception. The Romans regarded these crops as strategically important, not only for their nutritional value but also for their role in trade, taxation, and social life.

The production of wine and olive oil was oriented toward regional markets as well as the wider Adriatic area. Oil and wine were transported in ceramic amphorae, which served as standardized containers for trade. Such amphorae have been found in the underwater area of the Primošten aquatorium, confirming the integration of this region into ancient trade networks.

Although it is not possible to speak of direct continuity of individual vineyards from Roman times to the present, it is clear that the agricultural tradition of viticulture and olive growing has been deeply rooted in this area since antiquity. Later historical developments merely built upon this foundation, adapting it to new social and political circumstances.

Transport Networks and Roman Roads

Roman authority was not based solely on military power, but also on a highly developed network of roads that connected distant parts of the Empire. The wider Primošten area was integrated into this network through branches of major Roman roads linking key urban centers of Dalmatia.

Although the main arterial road did not pass directly through Primošten, secondary routes enabled efficient connections between the hinterland, the coast, and major centers such as Salona, Scardona, and Tragurium. These routes were essential for the transport of agricultural products, movement of people, and administrative control of the territory.

The presence of Roman transport infrastructure further supports the thesis of planned landscape management, in which no part of the territory existed outside a functional system. The Primošten hinterland thus became an active participant in the economic and transport life of the ancient world rather than a marginal periphery.

Maritime Routes and the Role of the Coast

In addition to land communications, maritime connectivity played an exceptionally important role. The Primošten aquatorium, with its natural shelters and protected bays, was well suited for temporary anchorage of ancient vessels. Capes and coves provided refuge from adverse weather conditions, particularly strong winds such as the bora and the sirocco.

Finds of ancient amphorae in the underwater environment indicate intensive maritime activity. Although there is no evidence of a major harbor in the area of present-day Primošten, it is clear that this space formed part of a vibrant maritime system linking the eastern Adriatic coast with Italy and the wider Mediterranean.

Maritime traffic enabled the distribution of local products, as well as the inflow of goods, ideas, and cultural influences. In this way, ancient Primošten—despite lacking an urban center—was integrated into the broader world of the Roman Empire.

Late Antiquity and the Transition to the Middle Ages

During late antiquity, gradual changes occurred in patterns of life and spatial organization. The weakening of central Roman authority, shifts in security conditions, and the gradual spread of Christianity influenced the movement of populations away from exposed coastal locations toward safer inland areas.

Communities increasingly withdrew to elevated and interior positions, where life continued in smaller, more defensible settlements. This process represents an important link between the ancient and medieval periods and laid the foundations for the later development of medieval settlements in the area known as Bosiljina.

The Middle Ages: The Formation of the Bosiljina Landscape and Life in the Hinterland

The transition from Late Antiquity to the Middle Ages in the area of present-day Primošten was not marked by a sudden rupture in the continuity of life, but rather by a gradual adaptation to new political, security, and social circumstances. With the weakening of Roman administration and the disappearance of centralized authority, the area remained inhabited, although the organization of life changed significantly. It was during this period that a medieval landscape took shape—one that would strongly determine the later development of the settlement.

In the early Middle Ages, life did not take place along the immediate coastline. The sea, which in antiquity had represented a space of communication, became a source of danger in times of increased insecurity. Piracy, political instability, and frequent changes of power encouraged the population to retreat inland, where a network of smaller settlements developed in the hinterland.

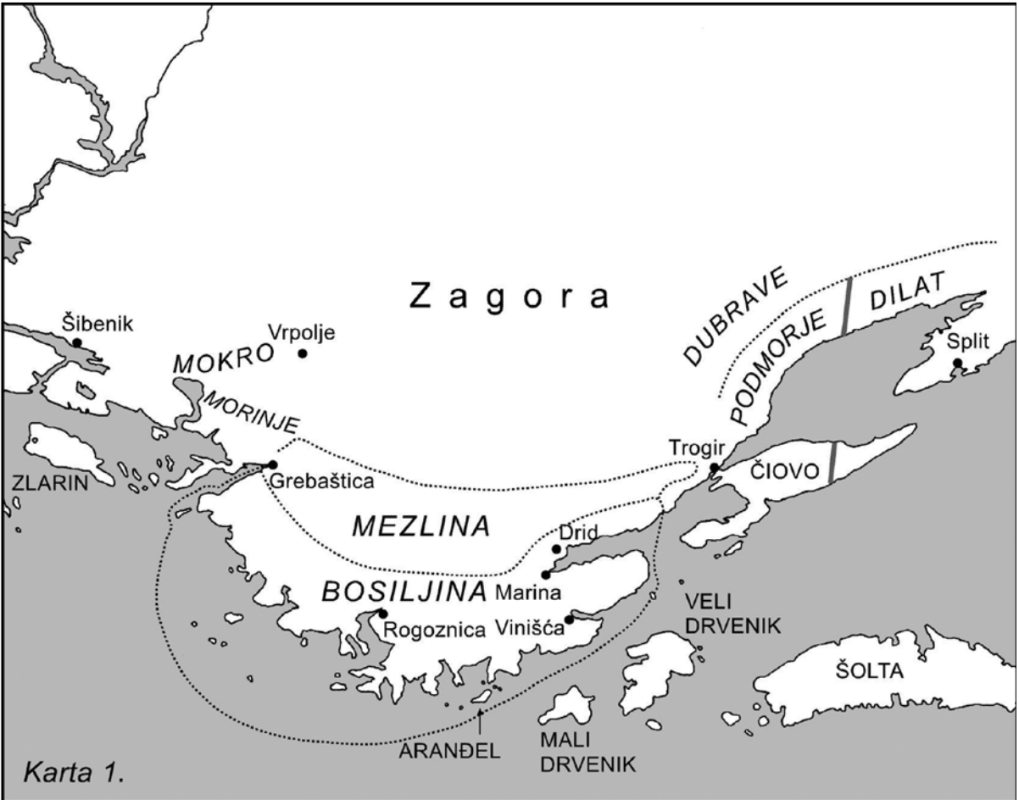

Bosiljina as a Medieval Spatial Entity

In the Middle Ages, the wider area of present-day Primošten and Rogoznica was known as Bosiljina. This name did not denote a single settlement, but rather a broader territorial and social space within which villages, churches, and agricultural land developed. Bosiljina encompassed a series of settlements located inland, on elevated terrain and in sheltered valleys, which enabled safer living conditions in uncertain times.

The earliest recorded settlements in this area include Prhovo, Kruševo, and Široke. These villages were not large urban centers, but organized rural communities based on livestock breeding, modest agriculture, and mutual solidarity. Stone remained the fundamental building material, and architecture was adapted to the karst terrain and limited resources.

The population of Bosiljina was closely tied to the land. Cultivation took place under difficult conditions, with a constant struggle against the scarcity of arable land and climatic challenges. Despite these constraints, it was precisely during this period that patterns of labor and social organization were consolidated—patterns that would remain present well into the early modern period.

Map illustrating the approximate territorial extent of Bosiljina, the medieval hinterland of present-day Primošten and Rogoznica

Political Framework and the Early Croatian State

Following the arrival of the Croats, the area of Bosiljina became part of the early Croatian state and, during the High Middle Ages, fell under the jurisdiction of various feudal and ecclesiastical authorities. The political framework of the medieval period was complex and fluid, characterized by frequent shifts in power and influence.

Bosiljina lay at the intersection of the interests of the noble families of Šibenik and Trogir and later became part of the broader Šibenik district. Although distant from major political centers, this area was not isolated. Feudal relations, taxation obligations, and ecclesiastical organization clearly shaped the everyday lives of the population.

Land tenure was based on a system in which land was owned by nobles, the Church, and urban communes, while peasants cultivated it in exchange for the obligation to deliver a portion of their produce. This system was not static but adapted to local conditions and the capacities of the population.

Church Life and Spiritual Centers

In the Middle Ages, the Church played a crucial role in shaping the social and identity framework of Bosiljina. Ecclesiastical buildings did not serve only religious purposes, but also functioned as centers of gathering, administration, and social cohesion.

Particularly significant was the Church of St. George in Prhovo, considered the oldest ecclesiastical center in this area. The parish of Prhovo ranked among the older parishes of the Diocese of Šibenik, established at the end of the 13th century. Its importance extended beyond the local level, as it served the population of the wider Bosiljina area.

In this period, Christianity functioned not only as a religious system but also as a stabilizing force in times of insecurity. The Church provided continuity, structure, and a sense of belonging—elements of crucial importance for communities exposed to frequent external threats.

Economy and Everyday Life in the Hinterland

The medieval economy of Bosiljina was modest but sustainable. It was based on livestock breeding and the cultivation of cereals, vines, and olives, to the extent permitted by natural conditions. Labor was organized within families and small communities, and survival depended on adaptability and collective effort.

Houses were built of stone, simple and functional, often grouped into small villages. The spatial organization of settlements was conditioned by topography, access to water, and arable land. In such an environment, a strong bond between people and space developed—a defining characteristic that would remain a lasting feature of the Primošten identity.

Coastal Insecurity and Preparation for Change

As the Middle Ages approached their late phase, security conditions throughout the wider Dalmatian region gradually deteriorated. The coast became increasingly exposed to external threats, while the interior, though relatively safer, could no longer guarantee long-term protection.

In this context, medieval Bosiljina entered a period of transition and uncertainty. These processes would ultimately lead to one of the most dramatic events in the history of Primošten—the organized relocation of the population from the hinterland to a small islet along the coast, marking the end of the Middle Ages and the beginning of a new historical era.

The Late Middle Ages: Relocation to the Islet and the Formation of a Fortified Settlement

The Late Middle Ages represent a turning point in the history of the area of present-day Primošten. Processes that had developed over previous centuries—life in the hinterland, reliance on karst agriculture, and the strong role of ecclesiastical structures—reached their limits in the second half of the 15th century. Security conditions throughout the wider Dalmatian region deteriorated dramatically, leading to a radical spatial and social transformation of the local community.

This period was marked by Ottoman advances toward the Adriatic coast, which fundamentally altered the way of life in the hinterland. Although the Ottomans never permanently occupied Primošten, their presence in the interior created lasting insecurity that directly influenced the decisions of the local population.

The Ottoman Threat and the Collapse of Hinterland Security

Following the fall of Bosnia in the mid-15th century, Ottoman military units began increasingly frequent incursions into the Dalmatian hinterland. These swift and destructive raids, aimed at plunder, the capture of inhabitants, and the destabilization of border areas, particularly affected rural settlements such as those of Bosiljina.

The villages of Prhovo, Kruševo, and Široke—centuries-long foundations of life in this region—became exposed to constant danger. Their defensive capacities were limited, and natural shelter was no longer sufficient to protect the population. Life in the hinterland became unsustainable, forcing the community to confront an existential question of survival.

Under such circumstances, the population made a decision that would permanently shape the history of the settlement: the abandonment of the hinterland and relocation to the coast.

The Islet of Gola Glava as a Refuge

The choice of a new place of residence was not accidental. The population selected a small, uninhabited islet off the coast, known as Gola Glava (often recorded in historical sources as Caput Cista). The islet was surrounded by the sea, with steep shores and limited access, making it ideal for defense.

The sea, which in earlier periods often represented a threat, now became a key element of protection. Access to the islet was possible from only one side, allowing for control of entry and effective defense against attacks from the mainland.

Relocation to the islet did not mean a severing of ties with the hinterland. On the contrary, the population remained dependent on their fields, vineyards, and olive groves inland. What changed, however, was the clear separation between living space and working space—residence and security were concentrated on the islet, while economic activity continued on the mainland.

Construction of the Defensive System

Following relocation, intensive construction of defensive infrastructure began. High stone walls were erected around the entire islet, adapted to the natural configuration of the terrain. These fortifications were not monumental in the sense of large cities, but they were functional, solid, and sufficient to protect a small community.

A particularly important defensive element was the wooden drawbridge connecting the islet to the mainland. The bridge was raised in the evening and in times of danger, completely isolating the settlement from the mainland. This simple yet effective security measure enabled a relatively stable life within the walls.

The walls and bridge were not merely physical structures, but symbols of a new phase of collective identity. Life behind the walls implied cohesion, mutual dependence, and a clearly defined spatial organization.

Urban Development Within the Walls

The limited space of the islet directly influenced building patterns. Houses were constructed densely, adjacent to one another, often sharing walls. Streets were narrow and irregular, shaped by natural topography and defensive needs.

This urban layout served multiple purposes. On the one hand, it allowed for maximum use of space; on the other, it hindered the movement of potential attackers. A network of narrow alleys (kalete) emerged, which still defines the recognizable structure of Primošten’s old town today.

At the highest point of the islet, the first church dedicated to St. George, the patron saint of the settlement, was built. Although modest compared to the present parish church, this structure held strong symbolic significance. The church became the center of spiritual life and a spatial landmark, visible from both sea and land.

Everyday Life Between the Walls and the Fields

Life in the newly founded settlement was strictly organized and followed a clear rhythm. During the day, inhabitants left the safety of the islet to work the land in the hinterland, returning within the walls at the first signs of evening. Such a way of life required discipline, cooperation, and mutual trust.

Despite constant danger, the community managed to survive and develop a stable way of life. This capacity for adaptation—rooted in collective experience and rational use of space—became one of the fundamental characteristics of Primošten’s identity.

The Name Primošten and the Symbolism of the Bridge

Although the settlement had existed for decades, the name Primošten appears in historical documents only in the mid-16th century. The name derives from the verb primostiti (“to bridge”), directly referring to the bridge as a key element of the settlement’s identity.

The name does not describe only the physical connection between the islet and the mainland, but also a symbolic link between security and labor, between sea and hinterland, between defense and survival. With this, Primošten ceased to be a temporary refuge and became a permanent settlement with its own name and a clearly defined character.

The Early Modern Period (16th–19th Centuryu): Stabilization, Venetian Rule, and the Shaping of the Landscape

With the onset of the early modern period, Primošten ceased to function solely as a refuge from external threats and gradually developed into a permanent, functional settlement with clearly defined economic, social, and spatial characteristics. The period from the 16th to the late 19th century was marked by a long process of adaptation—both to political circumstances and to the exceptionally demanding natural environment.

Following the firm consolidation of Venetian rule along this part of the eastern Adriatic coast, security conditions gradually stabilized. Although the Ottoman threat never disappeared entirely, its intensity diminished, allowing for long-term planning and more stable settlement development.

Primošten under the Rule of the Venetian Republic

During the early modern period, Primošten was governed by the Venetian Republic, which established a system of administration in Dalmatia primarily focused on protecting trade interests and maritime routes. Although a relatively small settlement, Primošten played a role within the defensive and economic framework of the Šibenik district.

Venetian authorities encouraged the maintenance of defensive structures while simultaneously imposing strict regulations on trade, particularly concerning products such as wine, olive oil, and salt. Despite these limitations, the local population demonstrated a remarkable ability to adapt, developing small-scale trade and maritime activities within the permitted framework.

At this time, Primošten did not possess the status of a major urban center, yet it gradually established itself as a stable and well-organized community whose life unfolded according to clearly defined rhythms—agricultural, religious, and maritime.ž

Early modern cartographic depiction of Primošten during the Venetian Republic

Spiritual and Spatial Culmination: The Church of St. George

In the mid-18th century, one of the key moments in Primošten’s history occurred with the construction of the present-day parish church of St. George. The older church, built in the late Middle Ages, could no longer meet the needs of the growing community.

The new church, completed in 1760, was built at the highest point of the peninsula, dominating the surrounding space. Its position was not accidental. In addition to its religious function, the church had a strong symbolic and orientational role, visible to sailors from a great distance.

The interior of the church preserves valuable altars and artistic elements, among which the veneration of Our Lady of Loreto stands out, gradually becoming the protector of the settlement. The Church of St. George thus became not only a religious center, but also the core of Primošten’s collective identity.

Demographic Growth and Spatial Pressure

During the 18th and 19th centuries, a gradual increase in population was recorded. Although living conditions remained difficult, relative security allowed for natural population growth. This, however, led to increasing pressure on the limited space of the former islet.

Dense construction within the old walls could no longer meet the needs of the community. Houses were expanded vertically, streets remained narrow, and quality of life was constrained by a lack of space, light, and ventilation. These conditions gradually encouraged considerations of spatial expansion beyond the old core.

Land Reclamation and the Permanent “Bridging” of the Mainland

In the 19th century, a crucial physical transformation of the settlement took place. As the Ottoman threat definitively receded, the wooden drawbridge lost its defensive function. Instead of the bridge, the space between the former islet and the mainland was gradually filled with stone and earth, permanently transforming Primošten into a peninsula.

This intervention had far-reaching consequences. Physical connection with the mainland facilitated easier movement of people and goods, opened space for urban expansion, and fundamentally altered everyday life. The former defensive character of the settlement gave way to a more open and functional spatial structure.

Land reclamation thus represented not merely a technical intervention, but also a symbolic end to one historical era. Primošten ceased to be a fortified settlement and began its transformation into a modern town.

Agrarian Transformation and the Creation of a Cultural Landscape

While Europe in the 19th century underwent the Industrial Revolution, Primošten experienced its own quieter but equally demanding transformation—an agrarian revolution carved in stone.

Due to continuous population growth and limited arable land, every fragment of soil became precious. The population began systematically clearing the karst terrain, manually removing stone to reach layers of red soil suitable for cultivation. The extracted stone was not discarded, but instead used to build dry-stone walls.

Thus emerged the unique vineyard landscape known as Bucavac—a network of regularly arranged stone-enclosed parcels that protect vines from wind and erosion. This landscape was not the result of formal planning, but of generations of labor, in which human persistence was literally inscribed into the land.

Viticulture and the Affirmation of the Babić Grape Variety

Within this agrarian transformation, viticulture became the foundation of Primošten’s economy. The Babić grape variety proved exceptionally resilient to dry and rocky conditions.

During the 19th century, Primošten’s Babić gained a reputation as a high-quality wine, appreciated beyond local boundaries. Wine production became not only a key source of income, but also a powerful element of identity, linking labor, landscape, and tradition into a coherent whole.

Emigration as a Consequence of Pressure

Despite progress, life in Primošten remained difficult. By the late 19th century, a combination of population growth, limited resources, and economic challenges led to mass emigration, particularly to overseas destinations.

Emigration became a lasting phenomenon that marked many Primošten families. At the same time, it enabled the economic survival of those who remained through remittances and the maintenance of strong ties with emigrant communities.

The 20th Century: Crisis, Emigration, and the Beginning of Modern Development

At the beginning of the 20th century, Primošten entered a new era as an extremely poor agrarian and viticultural settlement, whose survival depended almost entirely on nature, physical labor, and very limited economic opportunities. Despite a strong local identity and a long tradition of working the karst landscape, the early decades of the century brought a series of challenges that would profoundly shape the local community.

Historic photograph of Primošten at the beginning of the 20th century

Phylloxera and the Collapse of Viticulture

One of the most devastating blows to Primošten’s economy was the outbreak of phylloxera, a vine disease that swept through much of Europe’s vineyards at the beginning of the 20th century. The vineyards of Primošten—painstakingly created over generations—were not spared.

The destruction of vineyards had far-reaching consequences. Since viticulture formed the backbone of local subsistence, the loss of harvests led to sudden impoverishment. Within a short period, an economic system that had evolved over centuries collapsed, leaving many families without basic means of survival.

Emigration as a Strategy for Survival

Under such conditions, emigration became almost the only viable option. At the beginning of the 20th century, a strong wave of departures from Primošten was recorded, primarily toward the United States, South America, and Australia. Emigration was not driven by the pursuit of a better life, but by necessity.

Leaving for the unknown meant temporarily or permanently abandoning family, land, and community. Despite this, emigrants remained deeply connected to their homeland, and the money they sent back often became a crucial factor in the survival of those who stayed.

Emigration thus became an integral part of Primošten’s identity, leaving a lasting imprint on family structures, demographics, and collective memory.

Wars and Political Changes

The first half of the 20th century was also marked by major political upheavals. The First World War brought new suffering, mobilization, and further impoverishment. After the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Primošten became part of a new state entity, which brought administrative changes but little immediate improvement in living conditions.

During the Second World War, the Primošten area experienced periods of occupation, insecurity, and wartime losses. Despite harsh circumstances, the settlement managed to preserve continuity of life, relying on fishing, limited agriculture, and mutual solidarity.

War devastation further exhausted an already weakened community, yet at the same time strengthened a sense of belonging and resilience that would later play a crucial role in recovery.

The Post-War Period and the Beginnings of Renewal

After the end of the Second World War, Primošten entered a new political and social environment. The post-war period was marked by reconstruction and the search for new economic directions. Traditional agriculture could no longer sustain the growing population, while emigration gradually declined in intensity.

In this context, an idea emerged that would completely change the future of the settlement—the development of tourism. The sea, climate, location, and preserved old town were recognized as assets with potential far beyond local significance.

The Turning Point of the 1960s: The Birth of Tourism

The 1960s represent a key turning point in Primošten’s history. During this period, planned tourism development began, supported by both state authorities and the local community. Unlike the spontaneous tourism growth seen in some other destinations, Primošten opted for an organized and infrastructure-driven approach.

On the Raduča peninsula, the first major hotels were constructed, including Zora, Slavia, and Adriatiq. The development of hotel facilities created new jobs, stimulated service industries, and gradually transformed the social structure of the settlement.

Tourism did not immediately replace traditional occupations but gave them a new dimension. Fishermen, winegrowers, and farmers found additional sources of income, while younger generations increasingly turned toward professions linked to hospitality and services.

International Recognition and Cultural Openness

During the period of intensive tourism development, Primošten also gained recognition as a center of international encounters, particularly through gatherings of Esperanto speakers, which added a unique cultural dimension to the town. Visitors from different parts of the world came to know Primošten not only as a tourist destination but also as a place of exchange and dialogue.

In 1964, Primošten received an award for the best-arranged tourist town, confirming the success of its development strategy. This recognition carried strong symbolic value, marking the transition from a poor agrarian settlement to a community with a clear vision of the future.

The Bucavac Vineyards as a Symbol of Labor and Identity

Although tourism gradually assumed primacy, viticulture did not disappear. On the contrary, in the second half of the 20th century, the Bucavac vineyards acquired a new symbolic value. Photographs of these vineyards—created through generations of arduous labor—became internationally recognized symbols of human perseverance and adaptation to extreme natural conditions.

The placement of a photograph of the Bucavac vineyards in the headquarters of the United Nations in New York represented recognition not only of the local landscape but of the way of life behind it. Through this, Primošten entered the global context—not as a mass tourism destination, but as an example of a cultural landscape shaped by human effort.

The Homeland War and the Transition to a New Era (1990–2000)

At the beginning of the 1990s, Primošten, like the rest of Croatia, entered a period of profound insecurity marked by the Homeland War. Tourism, which had become the main economic pillar in previous decades, nearly ceased entirely. Tourist arrivals dropped sharply, hotel facilities stood empty, and many residents lost their primary source of income.

Despite this, Primošten remained a relatively safe area during the war and accepted refugees from conflict-affected regions. Once again, the local community demonstrated resilience and solidarity, drawing on survival experiences from earlier historical periods. The sea, fishing, and modest agriculture once again became essential elements of everyday life.

After the war ended, a process of recovery began. Tourism gradually returned, while the privatization of hotel facilities and the development of private accommodation altered the structure of the tourist offer. Primošten entered a new phase in which it faced the challenges of a market economy alongside the need to preserve its identity.

Primošten in the 21st Century: Identity, Branding, and Sustainability

Entering the 21st century, Primošten established itself as a highly recognizable destination where tourism, cultural heritage, and landscape complement one another. Development is no longer focused solely on increasing capacity, but on quality, spatial organization, and preservation.

Particular attention is given to the old town core, whose architectural structure is preserved as a cultural heritage site. Narrow alleys, stone houses, and public spaces become carriers of identity as well as foundations of the town’s tourist appeal. Spatial planning increasingly follows the principle of balance between contemporary needs and historical legacy.

International Recognition and Symbols of Contemporary Primošten

One of the most significant moments in Primošten’s recent history occurred in 2007, when the town received the prestigious “Golden Flower of Europe” award. This recognition confirmed decades of investment in spatial organization, horticulture, and quality of life, positioning Primošten among Europe’s most well-arranged tourist destinations.

In the 21st century, a new powerful symbol of the town emerged—the statue of Our Lady of Loreto on Mount Gaj. Installed in 2017, this monumental monument became a visible spatial landmark as well as an important spiritual and tourist destination. Its presence symbolically connects prehistoric, ancient, and contemporary dimensions of the landscape, emphasizing the continuity of human presence on the same elevations over millennia.

Bucavac as a Cultural Landscape of the Future

In the contemporary context, increasing attention is given to the cultural landscape of the Bucavac vineyards, recognized as a unique fusion of nature and human labor. The preservation of dry-stone walls, traditional parcels, and viticultural practices has become part of a broader discourse on sustainable development and heritage protection.

Today, Bucavac is viewed not only as an agricultural area but as a living monument to labor, whose value is measured in centuries of effort. This perspective enables the integration of tourism, culture, and agriculture, creating a development model that respects the past while looking toward the future.

Primošten Today: Between Tradition and Contemporary Life

Present-day Primošten is a place where multiple historical layers intertwine. From prehistoric hillforts in the hinterland, through a medieval fortified islet, to a modern tourist destination, the space has been continually adapted to new needs—yet never fully detached from its past.

Tourism is now the main economic driver, but awareness of the importance of preserving identity is growing stronger. This balance between development and protection represents the greatest challenge, but also the greatest opportunity for Primošten’s future.

Conclusion: Continuity of Space and Human Adaptation

The history of Primošten is not a story of sudden success or linear development, but of long-term adaptation. Over millennia, the inhabitants of this area have faced the limitations of karst terrain, political insecurity, and shifting economic models. Each generation has left its mark on the landscape—in stone, dry-stone walls, vineyards, and urban fabric.

From Illyrian hillforts and Roman agricultural estates, through medieval refuges and a fortified islet, to a modern tourist town, Primošten has developed as a space of continuity rather than rupture. This capacity for adaptation—rooted in labor, community, and understanding of place—forms the foundation of Primošten’s contemporary identity.

This historical overview demonstrates that Primošten is not merely a beautiful destination, but a cultural landscape in which nature and humanity have shaped a unique whole over centuries. Understanding that whole is essential for preserving the values that make Primošten distinctive—today and in the future.